Waste Colonialism

In the shadow of fashion's global supply chain, a quiet but pervasive form of colonialism persists. Known as "waste colonialism," this practice sees vast amounts of low-quality cast-offs from the Global North—disguised as charitable donations—flooding the Global South. Non-profit organisations, predominantly in the US, UK, Canada, and Germany, collect secondhand garments under the guise of 'keeping clothing out of landfill'. Yet, only 10% of donated clothing ends up resold locally within these markets; the remaining 90% is shipped to countries like Ghana, where nearly 40% of each bale ultimately becomes waste, unable to be repurposed. In Ghana in particular, home to the largest secondhand market in the world, Kantamanto, these discards have earned the name obroni wawu, or "dead white man’s clothes", a stark reminder of an overbearing colonial presence, that though seemingly 'a thing of the past', remains burdensome today. The weight of this environmental crisis falls heavily on communities that bare the least responsibility for fast fashion's excess, shifting the problem from the consumerism of wealthier nations to regions already grappling with limited resources (Mensah, 2023).

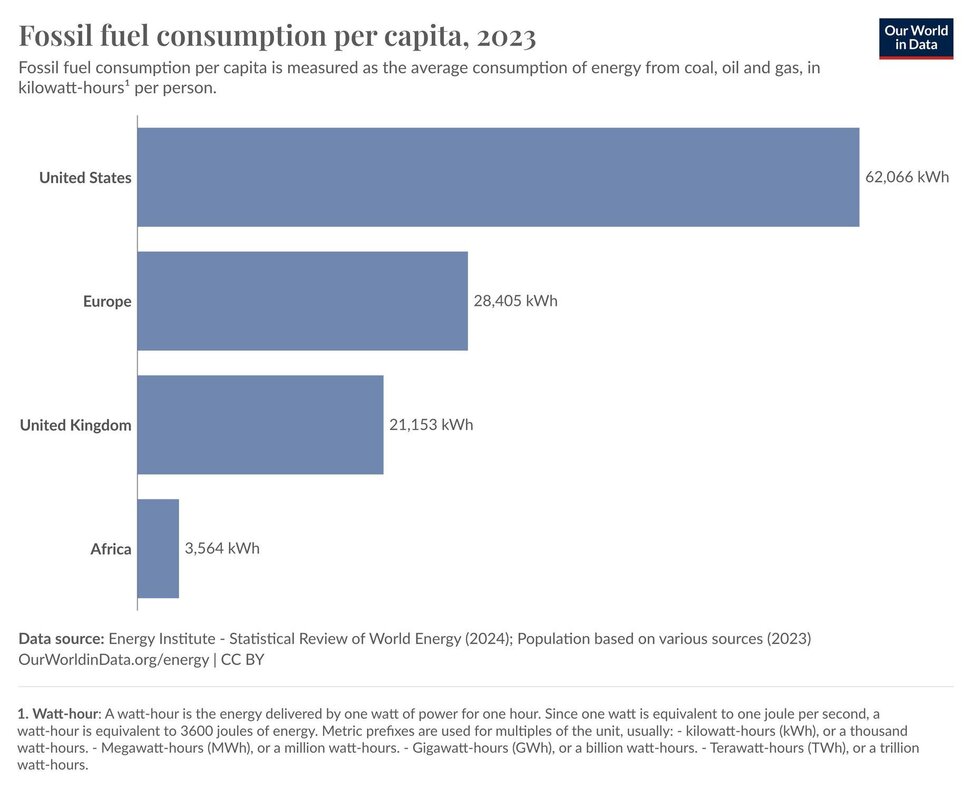

The Global South is often critiqued for utilising many of the same practices that earned the 'developed world' its economic rise; exploiting natural resources such as fossil fuels (Nartey, 2024). Meanwhile, the wealthiest regions, despite having greater economic means to invest in renewable energy, remain slow to adopt these changes, still leading global demand for fossil fuel consumption.

As the Global North's appetite for disposable fashion grows, so too does the need for true solutions that stop treating waste as someone else’s problem. At present, less than 1% of textile waste is fibre-to-fibre recycled due to a lack of scalable infrastructure to enable sorting and processing (McKinsey & Co, 2022). Keeping existing garments in circulation for longer, while offered as an alternative solution, is often rendered ineffective as new clothing continues to be produced.

While donating to charity and thrift shopping can, in such cases, create an often false narrative of sustainability, many African societies have mastered the art of resourcefulness instead. Their traditions of repair, repurposing, and upcycling—driven by necessity and self-sufficiency—showcase a circularity that often goes far beyond the surface-level solutions touted by Western recycling efforts. Their upcycled goods are valued for their originality and durability, offering a stark contrast to the fast fashion imports that fuel this waste crisis (Ellen MacArthur Foundation, 2023).

Words: Lydia Oyeniran

Reclaiming the narrative

Across the diaspora, this enduring approach to repair and reuse has been passed down for generations, extending across borders into Black communities around the world. Whether it’s that ice cream tub in the freezer, refilled with mum’s homemade stew, or the cupboard brimming with plastic bags (long before 5p charges were a thing), an anti-waste mentality has been a cornerstone of many Black households. Prior to upcycling having its fashion moment, clothing was passed from sibling to sibling, meticulously mended, and reworked until it was truly beyond repair. Rooted not only in necessity but a deeply ingrained culture of creativity and resilience, this ingenuity has shaped today’s Black fashion designers, now at the forefront of transforming sustainable fashion from bland to bold. From trailblazers like Dapper Dan, who pioneered the remixing of luxury fashion with streetwear, to the emerging talents featured below, this legacy of innovation continues to thrive. In celebration of Black History Month, we’re spotlighting the visionary designers who are reclaiming the narrative on waste through their heritage and homage to streetwear culture, revamping and re-working circular fashion with their upcycled creations—one stitch at a time.

Photo credit: @kemidanielle on IG

“Creative vision and sustainability can go hand in hand and actually, they complement each other and you can create something incredible that is better for the planet.” —Patrick McDowell (for Bricks Magazine)

Photo credit: @tegaakinola on IG

"I believe that everyone can contribute to a sustainable world, no matter how small it may be." —Tega Akinola

"Being environmentally and socially conscious is something that is very important to us, we want people to engage with the history of each garment, how it was made, where it has come from and, when they’re finished enjoying the piece, to be able to give it a new life." —Priya Ahluwalia

Photo credit: @priya.alhuwalia.1 on IG

"When I was growing up watching fashion shows, I loved their craft and the beauty of them [which] were amazing... But I was watching shows coming out of Paris, Milan, London and New York, and say they would do an “African” collection, or the “Chinese” collection, or the “Indian” collection, and they would just be like glorified costumes." —Priya Ahluwalia via Soho House

“Kick the bloody doors in, destroy, redesign, create something new”

Photo credit: Alhuwalia

Photo credit: @thriftqueenlola on IG

As these upcycled brands prove, fashion can be both resourceful and richly innovative. These Black British designers continue to redefine what it means to be truly circular, breathing new life into materials with bold, inventive designs. For other brands looking to make a similar impact, the journey to sustainability doesn’t mean sacrificing creativity. With CircKit's intelligent design tools, fashion brands can make smarter choices—selecting low-impact materials, balancing cost with environmental responsibility, and transparently showcasing their sustainability achievements. The future of fashion is circular, and technology can pave the way. Explore CircKit today and join the movement toward a more resourceful circular fashion industry.

Further Reading:

Making the most of materials: Africa's skills in repair and repurposing point the way for the Global North by Laura Collacott - Ellen MacArthur Foundation

The Global South as a Wasteland for Global North’s Fast Fashion: Ghana in Focus by James Mensah - American Journal of Biological and Environmental Statistics

Africa doesn't have a choice between economic growth and protecting the environment - how they can go hand in hand by Lite Nartey - The Conversation